Architectural Sketches and the Design Process – A Dialogue by Peter Brannan

Architects sketch to communicate to generate dialogue and the transfer of ideas within themselves and to the other participants involved in the design process.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a sketch as a rough or unfinished drawing or painting, often made to assist in making a more finished picture. In Ancient Greece, architects designed using words and precedent and consequently sketches are not mentioned in their history. Details were described by the use of Paradiegma – patterns or models, in reference to existing buildings, or components from them.

Recent excavations at Augustus’s Mausoleum in Rome show us that Roman Architects carved patterns and templates onto stone flagstones immediately in front of their buildings to direct builders on the cutting, fabrication and erection of stonework components for facades. Casts were made from components of previous buildings and conveyed to the site to help guide stone masons on the details required and envisaged by the architects. The Roman process was handed down to medieval builders and stone masons, who employed full-scale templates and models, but relied mostly on plans, in developing their techniques for design and construction.

Renaissance architects developed sectional perspective drawings along with plans and elevations. They also developed the use of wooden master models for the whole building as well as component mock-ups – often at full scale – based on sketches and studies prepared by the architects. Michelangelo’s use of sketches and mock-ups is well documented in the construction of St. Peters Basilica. Full-scale wooden mock-ups of cornices and other similar components would be hoisted into place for viewing and checking. Quite often the mock-up would not meet the expectations and would be taken down and replaced with a corrected mock-up based on rapidly prepared new sketches by the architect. The frustration of Michelangelo’s client, the Pope, in the delays and costs involved are also well recorded and provide us, perhaps, with the origins of the modern day claims process.

The records preserved from the Renaissance period provide us with the great sketches and drawings from Michelangelo, Leonardo, Brunelleschi and many others. It is a wonder to review these sketches. Paper was a valuable commodity in those times and was constantly used and re-used.

The records preserved from the Renaissance period provide us with the great sketches and drawings from Michelangelo, Leonardo, Brunelleschi and many others. It is a wonder to review these sketches. Paper was a valuable commodity in those times and was constantly used and re-used.

We can still trace the ongoing thought processes in the overlaid sketches and notes on these beautiful sketches of cornices, profiles and sometimes human forms interlaced within them. These records form much of the basis of the fluid design process depicted in architect’s sketches to the present day.

Evolution

The sociological and industrial transformation from the late Victorian and Edwardian periods into the modernist period after the First World War resulted in a new age in building and subsequently the way in which they were designed and built. The movement was led by architects like Le Corbusier, whose analytical approach ascribing function over form in the machine age is eloquently represented in his sketches and sketch books.

The sociological and industrial transformation from the late Victorian and Edwardian periods into the modernist period after the First World War resulted in a new age in building and subsequently the way in which they were designed and built. The movement was led by architects like Le Corbusier, whose analytical approach ascribing function over form in the machine age is eloquently represented in his sketches and sketch books.

A narrative of reason and philosophical purpose evolved, which was has been employed in the design of cities, buildings and products throughout the twentieth century and into the present period, as represented in the sketches and processes of today’s leading architects, like Norman Foster, Frank Ghery, Renzo Piano and others.

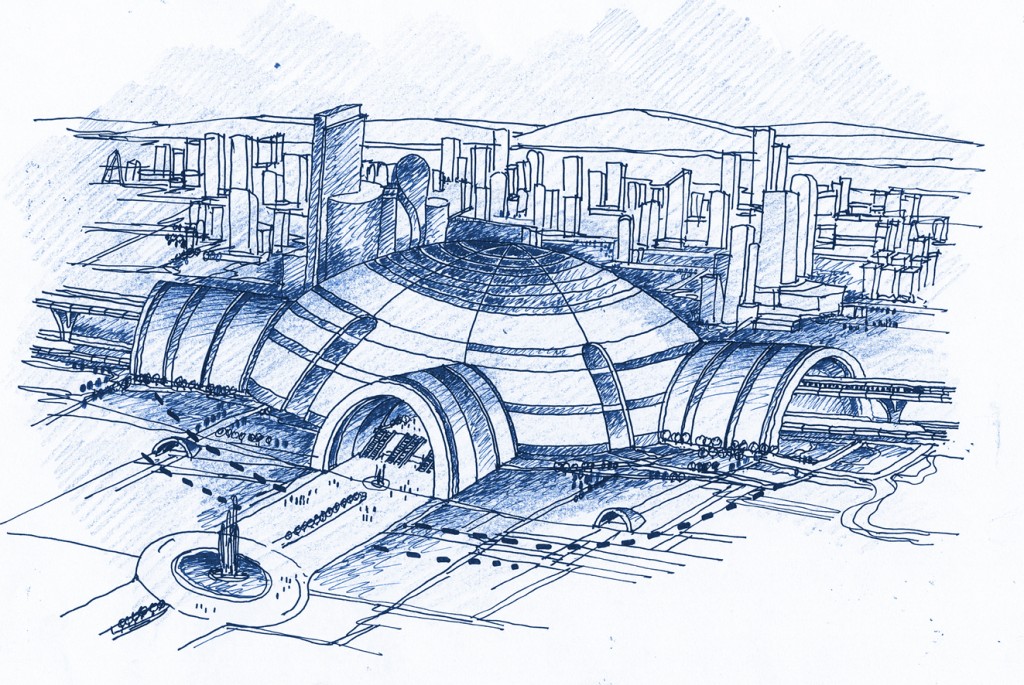

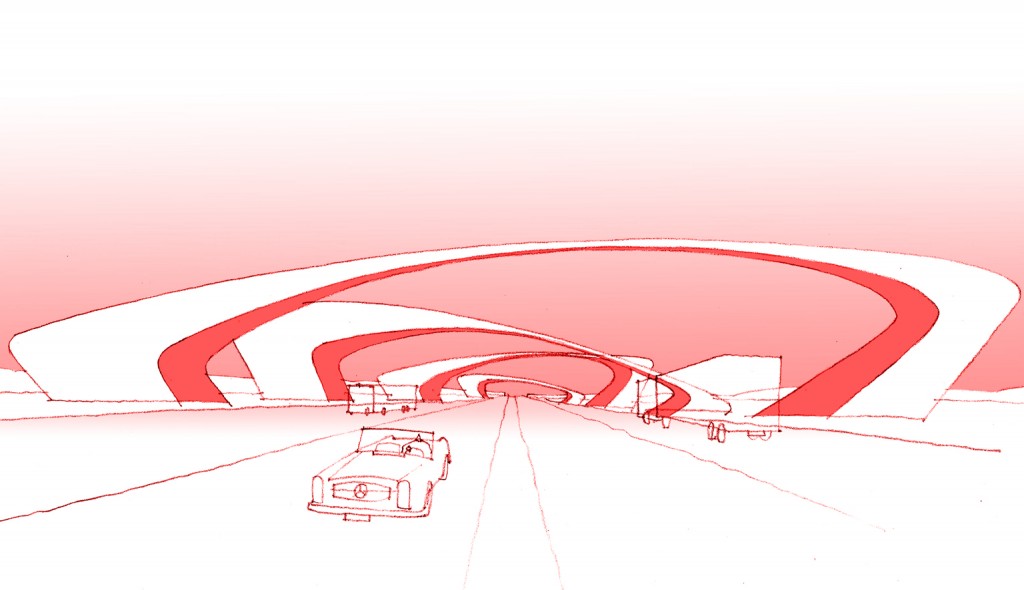

Sketches are produced for many purposes. They record images, ideas and inspiration the Architect draws from precedents, history or travel. They recall thoughts or musings for concepts yet to be realized, or they may be created specifically in response to the conceptual ideas inspired from a client’s aspirations and brief.

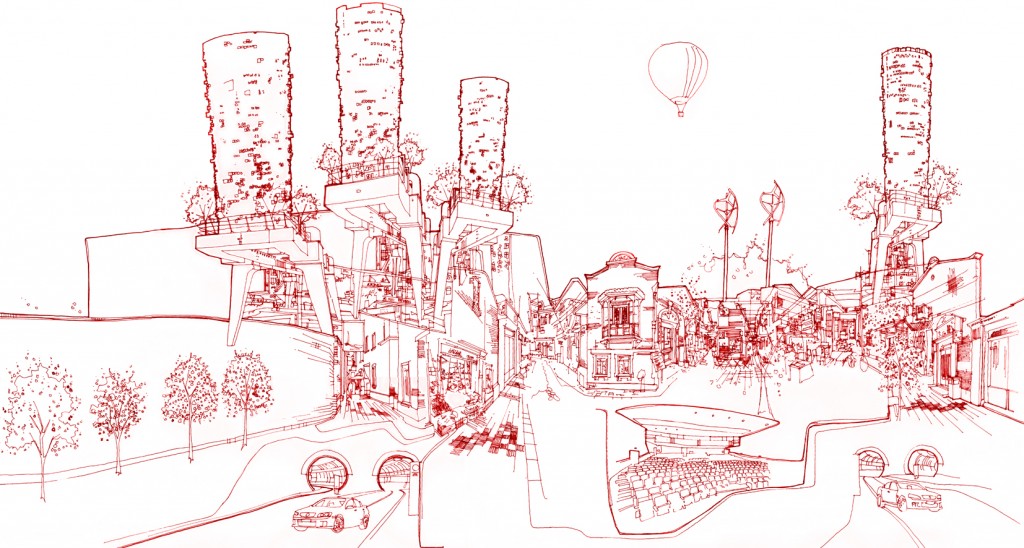

They communicate these ideas with colleagues, engineers, consultants, government authorities, contractors and the multitude of individuals and organizations involved in the design process, all the way through to final clarifications on the site or sometimes even corrections after construction is complete.

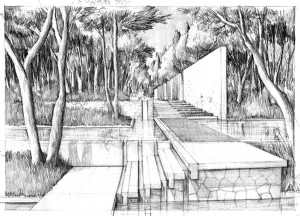

The design of a building involves resolving multiple problems on many levels, from the theoretical or philosophical in conveying allegory or nuance, to the physical or technical explaining the composition, pre-fabricated assembly or erection of components forming the whole. Sketches assist in understanding and conveying responses to these aspects and demands. Often commencing with an analysis of the response a building has to its site and surroundings versus its programmatic performance, through to the detail of a cladding component or the relationship of a brick in an arch.

The design process involves communicating with many people, some of whom may not be familiar with design and require customized explanations in the form of sketches or diagrammatic representations. Sketches form the thinking process that helps elucidate the ideas inherent in resolving these complex, often bewildering, problems. They help explain the solutions, or optional solutions, more clearly to those involved in a unique and self-explanatory manner that no other medium has yet surpassed.

The design process involves communicating with many people, some of whom may not be familiar with design and require customized explanations in the form of sketches or diagrammatic representations. Sketches form the thinking process that helps elucidate the ideas inherent in resolving these complex, often bewildering, problems. They help explain the solutions, or optional solutions, more clearly to those involved in a unique and self-explanatory manner that no other medium has yet surpassed.

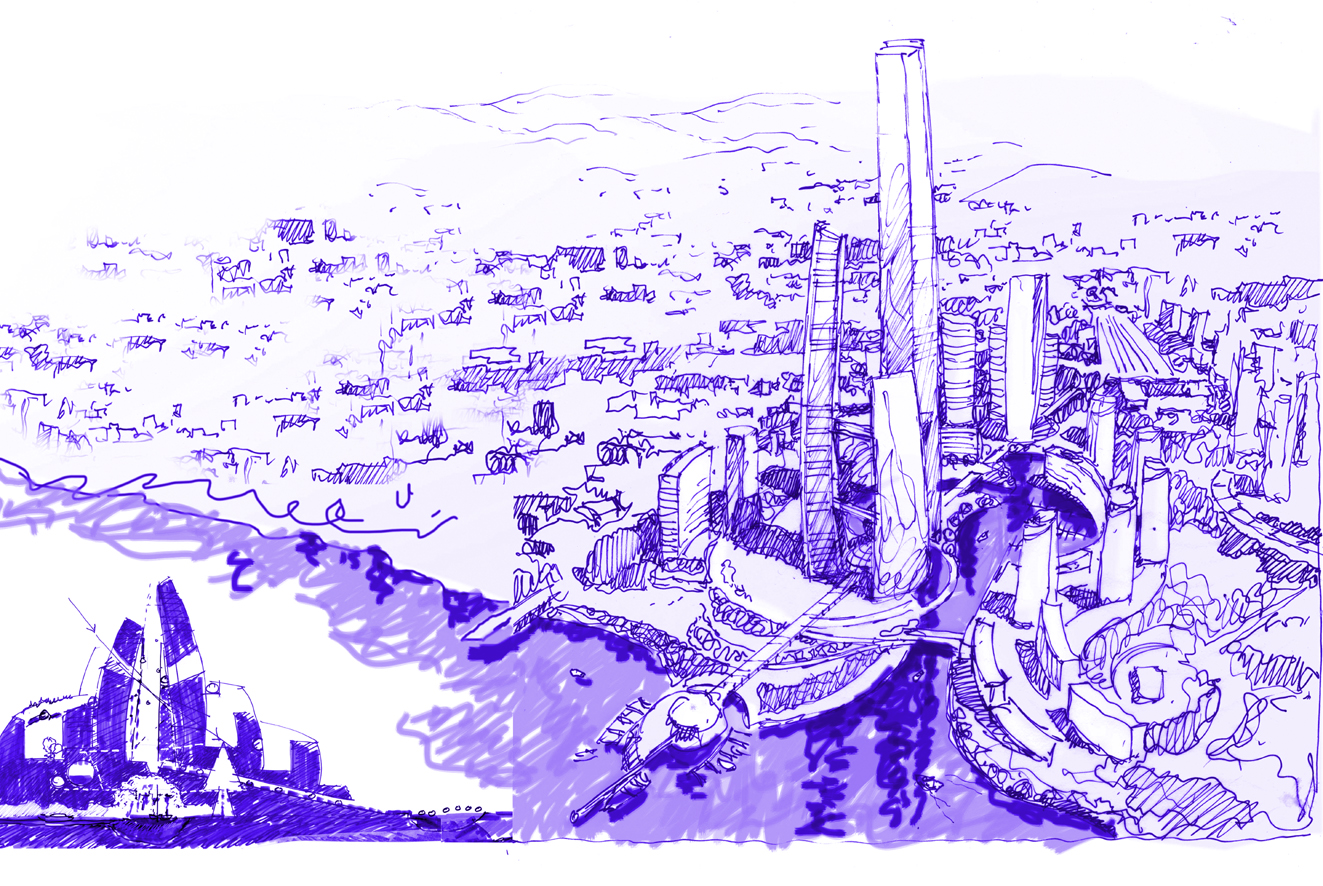

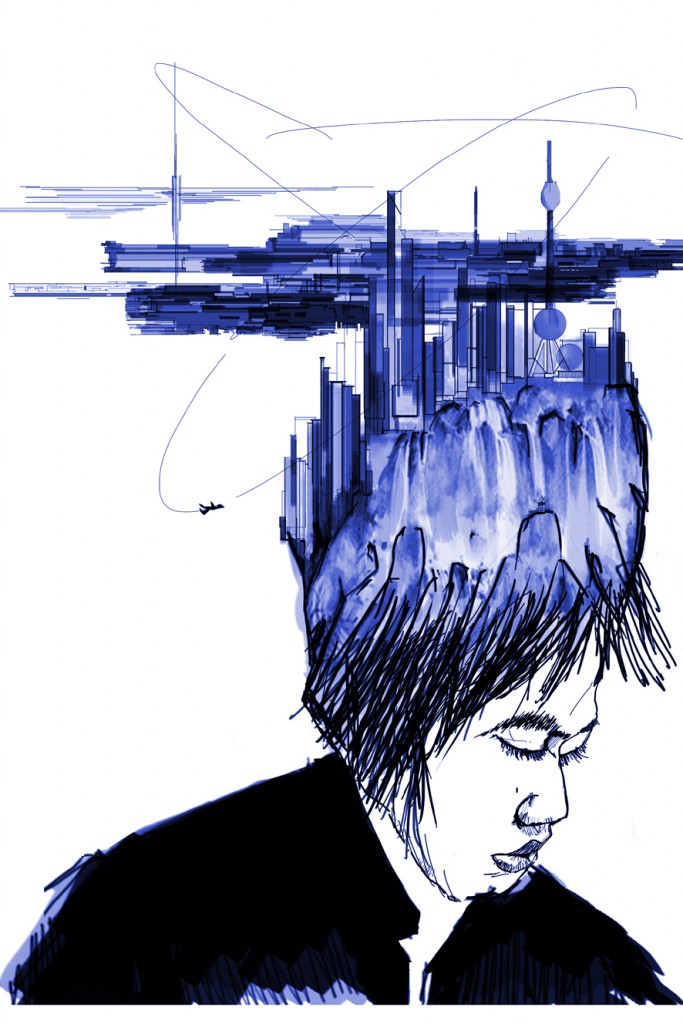

From the initial outlines of thought traced from the brain through the hand and onto a piece of paper, a conversation, or dialogue emerges – first with the creator and then with the others involved in the process. The dialogue is maintained throughout the process by the means of sketches. In many ways, the sketch becomes the dialogue. It will often start as an intimate, personal issue. It may appear stark, abstract or random. Numbers and notes mixed with apparent scribbles and quickly drawn lines of varying weight manifest themselves into a vocabulary of forms and shapes. Test fits and optional considerations are challenged and eked out. It is often a struggle. Gradually the solutions evolve through the haze and a clearer picture emerges.

Technology

Still, we live in an age of tremendous improvements in digital technology, which has transformed the design process and the construction of buildings and their components. CAD systems allow us to analyze and consider multiple options to design solutions previously impossible to contemplate. The application of technology is important. It improves design and the built environment we live in. It allows us to consider better options and alternatives and improvements in the way projects are delivered, managed and maintained.

Still, we live in an age of tremendous improvements in digital technology, which has transformed the design process and the construction of buildings and their components. CAD systems allow us to analyze and consider multiple options to design solutions previously impossible to contemplate. The application of technology is important. It improves design and the built environment we live in. It allows us to consider better options and alternatives and improvements in the way projects are delivered, managed and maintained.

However, technology itself changes at a bewildering pace and will continue to do so. The new generation of architects might be overly attracted to the technology, but it is essentially a transient tool, tailored to suit its various purposes in design. It does not alter the fundamental process of creativity and the utility of the sketch in the process. It might be a digital sketch, or it might be by pencil, but, no matter the seductive allure of powerful computer programs and sophisticated systems, or the trust placed in the humility of the tried and tested pencil on paper, the end product will always rely on the capacity of the person driving the process and creating the dialogue.

To mark the 10th Anniversary of PRC Magazine we wanted to peer into the minds of those who design the societies in which we live, work and play. The sketches featured here offer a profound insight into the way architects process ideas to develop solutions for an increasingly complex built environment. We are extremely grateful to all the busy professionals who gave their valuable time to join our anniversary celebration.

Publisher, PRC Magazine