The SKYCITY Transport Terminal by architecture and design firm Lead8 is situated within the highly anticipated 11 SKIES development in Hong Kong and has established itself as the primary transportation hub for the newly unveiled SKYTOPIA airport district.

With 16 franchised bus routes, taxi service lines, and additional transport facilities set to launch soon, the integrated transit terminal significantly enhances Hong Kong’s public transport network, connecting SKYTOPIA to Lantau Island, nearby border control points, Kowloon, and Hong Kong Island.

People-Centric Infrastructure

At the core of the SKYCITY Transport Terminal is a people-centric, experiential environment that redefines the conventional concept of what a large-scale, multi-modal transit hub can be. This design ethos transforms the terminal into more than just a piece of infrastructure; it becomes a holistic journey prioritising passenger comfort and creating a memorable sense of arrival and departure for the larger district.

“11 SKIES is a game-changing destination for Hong Kong. Our approach to the SKYCITY Transport Terminal was to ensure this gateway for travellers embodies the distinctive concept of the development,” shared Claude Touikan, Co-Founder & Executive Director at Lead8. “By drawing inspiration from the architecture and detailing of the scheme, we have crafted an arrival experience that encapsulates the vision of 11 SKIES and reimagines the potential of transit-oriented spaces.”

Designing an Experiential TOD Journey

11 SKIES is poised to become Hong Kong’s premier retail and travel-tainment landmark adjacent to Hong Kong International Airport. Following the successful completion of its first phase, K11 ATELIER 11 SKIES, the development plans to unveil additional attractions in the coming years, including eight world-class entertainment attractions.

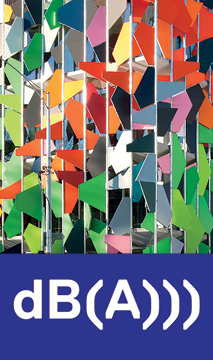

The design of the façades throughout 11 SKIES draws inspiration from these themes of flight and exploration, encapsulating the essence of movement and adventure. The SKYCITY Transport Terminal has adopted these design principles, continuing the articulated design that resembles paper planes, creating a distinguishing visual identity within the transit areas.

Feature Entrances That Welcome and Guide

Strategically located on the north, south, east, and west sides of the transport terminal, feature entrances have been designed as bold focal points providing efficient passenger flow and spatial orientation within the terminal. The entrances’ distinctive articulation and design language welcome visitors to the 11 SKIES retail development and make the terminal an extension of the overall development before even stepping inside.

“Our strategy for the feature entrances was to utilise the unique design of the articulated façades to create memorable gateways. Their bold design facilitates easy wayfinding, ensuring a seamless transition from the transit areas to the retail and entertainment spaces awaiting beyond,” explained Christopher Slater, Associate Director – Architecture at Lead8.

High-performance architectural coatings have been used for the architectural articulation to enhance the entrance’s visual appeal, with aluminium panels featuring a triple-layer polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) coating that accentuates the unique design language.

Acoustic Comfort and Creative Lighting

The thoughtful people-centric design extends to the terminal’s acoustic environment, significantly enhancing the overall travel experience. Most of the interior façades and wall panels are perforated and fitted with acoustic absorptive materials, effectively reducing noise transfer and fostering a calmer atmosphere for passengers.

The terminal lighting is another important part of the overall design approach, meticulously crafted to complement the architectural vision throughout the interiors. Feature ceilings over pedestrian areas utilise recessed lighting in an alternating pattern, which enhances the triangular features while also contributing to trouble-free wayfinding. This careful lighting approach ensures that every aspect of the terminal contributes to an engaging and cohesive experience for all visitors.

More Than a Transport Hub

The SKYCITY Transport Terminal redefines what a transit hub can be. By prioritising experiential design principles, Lead8 has created a space that is not only functional but extends the vision of the landmarks it supports. With a people-centric approach to transit-oriented design, the development aims to set a new standard for how transport facilities can engage with and inspire the public.

11 SKIES Facade Concept Drawing

Project Details

Location: Hong Kong, China

Architecture & Planning: Lead8

Interior Design: Lead8

Signage: Graphia

Executive Architect: Ronald Lu & Partners

Acoustic Consultant: Campbell Shillinglaw Lau Ltd

Lighting Designer: LPA

Lighting Contractor: SM C2R (Hong Kong) Limited

Façade Contractor: Condo

Traffic Planner: ARUP

Structure Engineer: AECOM

Mechanical Engineer: AECOM

Client: New World Development Company