A drive for more sensitive development that preserves Hong Kong’s built heritage is ensuring that city’s administrative, financial and social fabric are preserved.

Consumers, constructors and clients have come together to question Hong Kong’s progress and pitfalls in preserving heritage buildings. The RICS International Heritage Conservation Conference, held in January at the Hong Kong Jockey Club, heard a series of moderated discussions on the successes and challenges of heritage protection. Two recent reprovisionings, one on each side of the harbour, make great case studies.

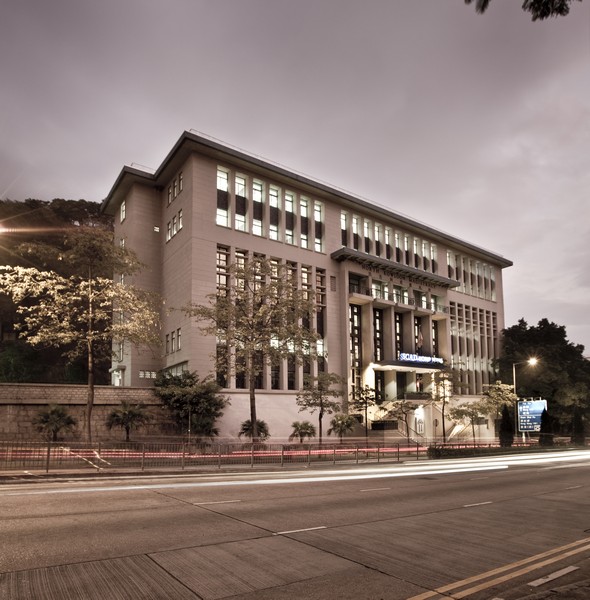

The Savannah College of Art and Design Hong Kong is based in the North Kowloon Magistracy building in Sham Shui Po. It is the only surviving example of neoclassical architecture in Hong Kong.

It was designed by Palmer and Turner Architects, built in 1960 and decommissioned in 2005. In the 1970s, thousands of illegal immigrants passed through its doors to obtain residency under the government’s Touch Base policy.

SCAD Foundation Hong Kong Ltd won the bid to revitalise the magistracy via the Revitalising Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme. A year later, in 2010, the former magistracy opened as Savannah College of Arts and Design Hong Kong. It was awarded the 2011 UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Award for Culture Heritage Conservation, among other awards.

The campus hosts 600 students from 30 nations, with half of the student body from the United States or elsewhere. SCAD HK vice-president Robert Dickensheets says his organisation has extensive experience in heritage preservation gained from revamping campuses in Savannah and Atlanta in the US, and at Lacoste in France.

Starting out

SCAD, Hong Kong

The North Kowloon Magistracy building was dilapidated when handed over for revitalisation. Floors were in disrepair, ceilings were falling in, and mould and dirt clung to the interior. Dickensheets saw the building’s promise.

“The more we cleaned, the more we conserved, when we put the lighting in, the nature of the building changed from being a courthouse to almost a museum-like environment worthy enough to bring in great artwork and to showcase student works,” he says.

Apart from obvious concrete spalling, the magistracy had withstood 50 years of use and weathering. The wide columns supporting the 7,000-square-metre structure dictated its redesign and extent of reconfiguration.

Among the original aspects carefully preserved are the bronze-studded panel doors at the main entrance, the natural granite staircases with Grecian-motif balustrades, the main courtroom and one original detention cell as part of its contract.

Inside Courtroom No.1, its original components have been immaculately preserved, from its benches to its doors and ceiling panels, down to the worn-down bronze surface of the security bars.

Surround sound audio equipment and large screen television were installed for its new function as a major lecture hall. One detention cell has been kept in its original condition, while the remaining ones have been “modernised” into meeting rooms and office space.

Structure first

Portions of the buildings with little preservation value, such as the bulk of courtrooms and offices, have been reconfigured into classrooms and learning spaces. To prevent damage to its cast concrete walls and retain the original beams, cloud ceilings and ducts for lighting, fibre optics and air conditioning have been installed throughout.

SCAD, Hong Kong

SCAD sees itself as an educational museum on adaptive reuse, heritage preservation and community involvement. From opening day onwards it began giving tours to students, local residents, academics and professional architects alike. In a typical week, academics will visit to inspect its heritage while architects come to talk about adaptive reuse. The school also operate cadet programmes and community access workshops.

“Letting the building be part of the design process, rather than being a recipient, allow its structure and important decorative elements to live on and find new uses,” says Dickensheets. “All too often in adaptive reuse, people just use the building as a shell for a whole new design concept which doesn’t always work. The building in a sense, tells us what it can become. And that is the most important part of adaptive reuse.”

Mr Paul Chan, JP – Secretary for Development

Saved from demolition

The former Police Married Quarters flanked by Hollywood Road and Aberdeen Street, reborn as PMQ, was perilously close to being auctioned off for residential development before its inclusion in the Conserving Central master plan in 2009.

The building went up in the 1950s, on the foundation of the Central School, the first Western school in Hong Kong and an institution that was pivotal to China’s modernisation.

The police quarters were a Grade III historic building. The structure housed married frontline policemen and served as the prototype for public housing.

Its elevations and interiors were typical of post-war functionalism. The original buildings featured plentiful balconies and a spacious courtyard, both rarities. Kitchens and dining areas were conveniently located in the corridors. Individual bathrooms, as well as elevators were added as part of an amenities upgrade in the 1970s.

Its vicinity to SOHO, a lack of public space and concerns over view and ventilation obstruction in Mid-Levels forced the government to revamp the property.

Rule of threes

PMQ central countyard including the original Central School foundations

PMQ has three buildings, two of which were the living quarters and a recreation centre. The refurbished site was envisioned to be a self-sustaining creative landmark and design platform that contains retail and commercial spaces for a mix of related industries such as architecture, graphics, branding, retail and apparel design. It is perceived as being a wholly commercial endeavour.

The revitalisation project was awarded to the Musketeers Foundation in collaboration with Hong Kong Design Centre, Hong Kong Polytechnic University and Hong Kong Design Institute of the Vocational Technical Institute.

The team was expected to achieve three objectives: promoting the development and status of the city’s creative industries, conservation of the current structure, and the provision of open space.

“Our department began soliciting input from the winning bidder as early as the scheme phase in order to enhance its viability from an operational and sustainable development standpoint,” says Architectural Services Department deputy director Stephen Tang. “It only took slightly more than two years from construction to occupation, which for a heritage project was considered extremely quick, and is probably fastest in the world.”

The department ensured the external façade stayed intact or was restored. Tang says procuring identical steel window frames and out-of-production handles was particularly troublesome. Structurally, the podiums and foundations were sound, except for a few leakage areas that have been repaired.

During the construction phase, the department frequently modified its plans where the old Central School foundations were discovered. Preserved in their original site, a chamber has been added for protection and to provide the public with a clear view of the foundations that date back to the 19th century.

Internally old stairwells have been expanded while new ones have been added, along with a massive upgrade of mechanical, electrical and plumbing to comply with the latest commercial building codes.

Responding to criticism that PMQ is overly commercial and lacks adequate public space, the department says the glass canopy above the internal courtyard creates a weather-proof outdoor space, and additional public space on the site’s north edge is free of charge.

The clustering of diverse talents at PMQ facilitates cross-discipline collaboration and to foster a sense of community PMQ maintains an open door policy from 1 to 10 pm.

Public involvement

Public opinion has become a force to be reckoned with, to the point of influencing policy making related to heritage conservation. Focus is evolving from simply preserving individual historical buildings to include entire districts and intangible heritage.

PMQ Night Market

There is no better example to illustrate the importance of sufficient public consultation and incorporating community input when designing for heritage preservation than the recent renovation of St. Andrew’s Church.

The church’s century old stone walls facing onto Nathan Road, though not part of the heritage listed site, had long been considered integral to Tsim Sha Tsui’s streetscape. Their demolition and slope excavation in 2012 to construct a Life Centre was hardly controversial. Nevertheless, the completion of the project two years later generated widespread criticism. The loudest complaints being that the newly elevated granite facade has obstructed passer-by’s view of the church and is incongruent with its surroundings, and that replacing the public green space with a “landscaped” cement rooftop for the new structure is at best, tasteless.

Of the seven landmarks that constituted the “Conserving Central” master plan, PMQ was the first completed project; new design plans for the Murray Building have been submitted for government approval that will see a radical overhaul of its interiors and podium; currently in the design stage, the former Central Government Offices Complex will be repurposed as new offices for the Department of Justice, whilst former French Mission building will be preserved as a legal services hub for arbitration and mediation, and office space for NGOs. The future of Hong Kong’s prized Bauhaus icon, Central Market remains an open question, and in 2016 The Hong Kong Jockey Club’s HK$2.4 billion renovation of the former Central Police Station will be complete.

One thing is now certain, with each and every adaptive re-use or major revitalisation of Hong Kong’s old buildings to take place from here on in, the very mention of the word heritage will be sure to impassion a public that wants our city’s past to be preserved with purpose and dignity. There is a fresh understanding of just how much the built environment can contribute to our society’s newly confident sense of self.

From L to R: Otto Ng, Director of LAAB, Mr. William Tsang, Architect (ASD), Mr. Stephen Tang, JP, Deputy Director of ASD, Mr. Victor Tsang, Executive Director of PMQ.

Hailing from the Philippines, senior interior design student, Isa Caruncho, says she mainly chose SCAD for its heritage properties which provides her with a sense of place that a brand new building cannot.

“The campus has drawn me into pursuing preservation as a future career path. You are preserving the past and creating something new at the same time. This requires imagination, and a new building simply doesn’t offer this sort of juxtaposition.”

Otto Ng’s interior design and architecture firm, LAAB, works out of a unit on the sixth floor of PMQ.

“The clustering of diverse talents at PMQ facilitates cross-discipline collaboration and nurtures the kind of creative sparks unattainable through social media. Just recently, I worked with the fashion designer next door to my office on a new piece of artwork. “