In today’s world there is much talk on the topic of diversity and inclusion. But what does that mean in the world of architecture and property development? Perhaps we should look back to 1988, when American architect, product designer and educator Ronald Mace, best known for his work advocating for people with disabilities, coined the phrase ‘universal design’, which he referred to as “the design of products, environments, programmes and services to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.”

(按此瀏覽中文版)

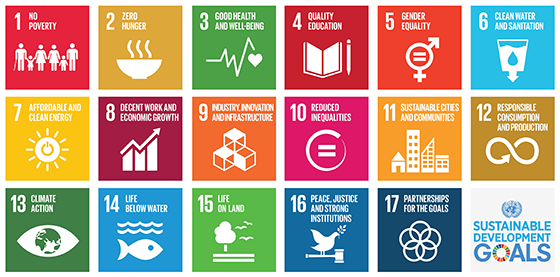

Fast forward almost three decades to a presentation made in 2017 to Hong Kong’s Architectural Services Department (ArchSD) by architect and accessibility consultant Joseph Kwan titled ‘A Global Perspective on Inclusive Environment’, which opened with an opinion on the shortcomings of the UN’s Millennium Development Goals and tracked the progress through to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) laid out and designed to transform our world by 2030.

Of these, Goal 11 sets out to make “cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”, which is particularly apt in its reference to access for all to safe and affordable housing, sustainable transportation systems, and green and public spaces, including persons with disabilities. He also referenced the Incheon Strategy, developed over more than two years of consultations with governments and civil society stakeholders, which charted the course of the Asian and Pacific Decade of Persons with Disabilities for the period 2013 to 2022, designed to strengthen the 2030 Agenda.

Since then Kwan notes that numerous agreements have been made globally at summits taking place from Istanbul to Ecuador to address issues relating to the inclusion of disabled persons within the society. These events have culminated in the formation of the Global Network on Disability Inclusive and Accessible Urban Development (DIAUD), a multi-stakeholder network focused on building and enhancing networking among persons with disabilities and disability rights advocates, policy makers and government officials.

Putting people first

There is no denying that Kwan is a true ambassador for universal accessibility (UA). His passion shines bright. As an architect, he says that his drive comes not only from shape and form, but also for a real desire to design for people. His study of environmental psychology in London might be seen as a catalyst for his work in UA, followed by his return to Hong Kong in 1987 where he worked on his first UA project before establishing his own practice and becoming director of an NGO working to promote accessibility in the city.

Kwan was also instrumental in initiating the accessibility of Tuen Mun Park, under the Playright Children’s Association, of which he has been a board member for over 30 years.

“Governments, urban development professionals, academia, foundations, the private sector and development cooperation partners all have their part to play in driving the way forward in the future of universal design,” he says in an interview with PRC. And whilst he recognizes that countries such as Canada, Norway and the US have made significant steps in incorporating universal accessibility through governmental legislation, he adds that Asia and Europe still have a long way to go when it comes to achieving a safe, inclusive, resilient, sustainable and socially responsible built environment for all.

Greenlighting accessibility in the Greater Bay Area

Kwan notes that positive steps are being made in China, driven by Beijing’s support for the China Disabled Persons Federation (CDPF). Kwan, in his role as government UA advisor, has been actively promoting the agenda not least by giving presentations at a governmental level in Beijing and Shanghai and in cities across the Greater Bay Area.

“Beijing’s hosting of the Olympic and Paralympic Games in 2008 was a real turning point for China in terms of highlighting the value of universal accessibility. It’s encouraging to see that in the past year the Greater Bay Area has tuned into our agenda. I hope that the initiative will lead to greater traction, more concrete regulations and the design and building of more accessibility across southern China’s cities. That said, much more needs to be done.”

Today, in his role as advisor and accessibility consultant for numerous bodies, Kwan can at least take some credit for the progress that has been made in Hong Kong. Largely this has been through modifications to ArchSD’s practice notes which have resulted in all government buildings now having to comply with their universal accessibility requirements in addition to the minimum standards set out by the government’s Buildings Department, Design Manual – Barrier Free Access 2008

Taking the lead

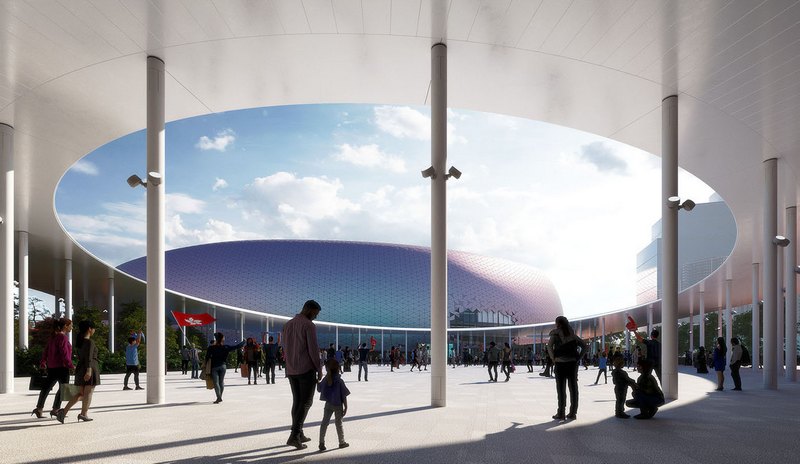

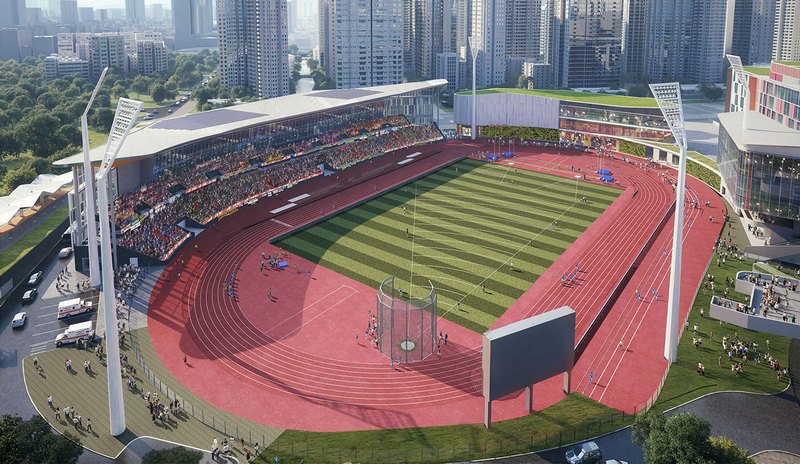

Projects such as the highly-anticipated Kai Tak Sports Park, led by Hong Kong’s Home Affairs Bureau, and where Kwan has been involved in the writing of the universal accessibility requirements into the design brief and masterplan, is a case in point.

“I’m please to say that the project has very solid guidelines within its design manuals and we’re looking very hard at accessibility at a much higher level. We not only need to consider accessibility for the disabled, those hard of hearing, visually impaired or the mentally challenged,” he says. “We are also considering the mobility needs of an ageing society and the advantages of accessible tourism in all our public spaces.”

Other government projects under construction with better access provisions include the Palace Museum and East Kowloon Cultural Centre.

Within the private sector perhaps more developers need to follow the example of Link Asset Management Ltd, managers of Hong Kong’s largest real estate development trust, which added former government owned residential properties and over 180 once derelict shopping centres and carparks to its portfolio over a decade ago. Kwan was engaged as an accessibility consultant to upgrade all their assets to the level of minimum accessibility, resulting in an estimated increased footfall of up to 30%. The retrofitting works to improve barrier free access was a 6-year program at a total cost of HK$220 million. Staff disability awareness and sensitivity training was an integral part of the program introduced by Kwan, as an equally important component to inclusion and socially responsible built environment for all.

But ultimately Kwan believes that significant progress can only be achieved if it is government led.

“If we are going to make real progress within the private sector the Hong Kong government needs to provide incentives for developers and architects to do more, for example by offering tax incentives or something similar to the green building initiatives that were introduced in return for additional GFA,” he says.

“We need to drive things forward with rules and regulations that are apply to 2021 standards. This requires a review of the Hong Kong design manual, which hasn’t been updated since 2008. It’s a slow process and we cannot simply rely on architects and developers to move beyond the minimum governmental standards.”

A consideration of accessibility for all also needs to become more than just a CSR box ticking exercise. “Moving forward there needs to be a real push within the architectural industry towards promoting UA as a specialized area of expertise necessary for every practice and developer in the city,” he concludes.