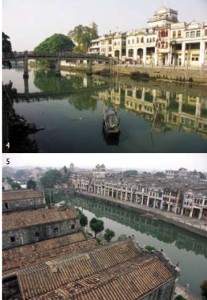

While Hong Kong races to build the biggest, glossiest and tallest buildings on the block, it also endeavours to acknowledge the structures that date from the city’s earlier days.

While Hong Kong races to build the biggest, glossiest and tallest buildings on the block, it also endeavours to acknowledge the structures that date from the city’s earlier days.

“To strike a balance between new development and onservation is key,” believes Eric CM Lee, director of LWK & Partners Architects and conservation expert. “Hong Kong has come a long way but this is a conflict that most cities face.”

Historic foundations

Conservation laws in Hong Kong date back to the 1930s. The Town Planning Ordinance legislation was enforced in 1939 and resulted in a planning survey. Concern about the extensive slum conditions in parts of the colony lead to the formation of an investigatory housing commission by the government. Many years later, the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance was established in 1976, followed by the Urban Renewal Ordinance in 2001 and the Environmental Impact Assessment Ordinance in 2007.

“When I was starting out, I never thought about working with conservation projects. At the time, the market trend was all about redevelopment because that was much easier and more profitable,” says Lee who is chairman of the Heritage and Conservation Committee of HKIA and holds a masters degree in architectural conservation from Hong Kong University.

“Even after 1997, the government was not too concerned about conservation policies. They still allowed developers to pull down classics like the Old Canton Railway station in Tsim Sha Tsui and replace it with a cultural centre,” Lee remembers. “Now a museum stands next to the railway station when really that historic Old Canton Railways station building would have been the perfect way to house a museum. ”

Lee recalls another historic building that’s rural landscape dramatically changed with urban development, the old Tung Chung fort that was built during the Chinese Qing Dynasty on Lantau Island. “When I first visited the old Tung Chung fort, we were facing the coastline with rows of paddy fields and British housing ahead.

Lee recalls another historic building that’s rural landscape dramatically changed with urban development, the old Tung Chung fort that was built during the Chinese Qing Dynasty on Lantau Island. “When I first visited the old Tung Chung fort, we were facing the coastline with rows of paddy fields and British housing ahead.

Now if you go to Tung Chung, you can just see a huge wall of housing blocks. So clearly, urban encroachment has had a huge impact on Hong Kong’s rural setting.”

The fort was built by the government to prevent smugglers bringing in salt from Hong Kong Island to Canton City. Three hundred soldiers were stationed to in Tung Chung fort.

The Japanese later lived within the arched gateways and muzzle-loaded canons of the fort during World War II. In 1970 the Tung Chung fort was declared a monument and in 1988 it was refurbished. However, now the island is host to Hong Kong International Airport as well as a flurry of residential compounds that have sprouted up in recent years.

The Japanese later lived within the arched gateways and muzzle-loaded canons of the fort during World War II. In 1970 the Tung Chung fort was declared a monument and in 1988 it was refurbished. However, now the island is host to Hong Kong International Airport as well as a flurry of residential compounds that have sprouted up in recent years.

Has the conservation landscape changed in Hong Kong?

Lee says that while there are only a few firms in Hong Kong that specialise in conservation, there is increased awareness among developers. “The change has been in the last 10 years. It’s the younger community that is demanding for more conservation awareness from the government. This generation wants to retain Hong Kong’s local identity and the best way to do this, they feel, is to preserve the monumental sites and buildings. An example is the Star Ferry Pier protests in 2006 – and it worked.”

“It’s difficult to just survive in heritage here in Hong Kong. You need to be an established firm. And you need to find profitable projects which are rare in conservation.”

“It’s difficult to just survive in heritage here in Hong Kong. You need to be an established firm. And you need to find profitable projects which are rare in conservation.”

LWK prides itself in being one of the few firms that have dedicated a department to heritage projects in Hong Kong. From the 13 projects that have been labelled for adaptive use, the Peak Lookout is one of them. The former train station was converted into a quaint, rustic chalet-style restaurant where its mountainous surroundings and its wooden floors, open fireplace and stone walls compliment the architecture perfectly.

Another project that was restored and adapted for commercial use is the Old Tai O Police Station. It was built in 1902 and its main focus was to combat piracy and smuggling from surrounding waters. The colonial style blocks which formed the police station was downgraded to a patrol post in 1996 but in 2002, it was vacated. So far, LWK have completed 4 heritage and 4 restoration projects.

The obstacles

“Money is pouring in for projects that involve public buildings, but where is the incentive to restore private buildings? That’s the problem. No one will think of demolishing Chinese ancestral halls because ownership is common. It belongs to different public entities so by virtue, it’s protected. But in Hong Kong, where land value is so high, we need to give developers of privately owned buildings enough economic incentive to renovate and restore instead of tearing down.”

What’s the solution?

Looking at other countries in Asia, Lee points to Singapore’s holistic approach where decisions such as land ownership, building and planning approval can all be made by a centralized authority. He also notes the use of tax exemptions as an effective tool to encourage private owners to practice conservation in the US. “For Hong Kong, we need to implement a mechanism that allows developers or building owners to transfer the development rights to other sites. Then, it’ll be easier to strike the balance. Adaptive reuse of these historic buildings for commercial use is also a much more realistic way of preserving them. In other cities, historic buildings have been converted into art galleries, restaurants and hotels. In Hong Kong however, people need time to get used to the idea of the versatile nature of such monumental historical buildings. It’s a matter of mindset.”