“Your cabin crew is here for your safety” is a familiar sounding sentence to many frequent flyers whom, over the past few weeks (if not months), may have longed for such an utterance as they remained locked down in their homes. If they are like me, they may be itching to get onto that first flight to (_____), feel the comfort of a blanket, a cold glass of something sparkly and the prospect of a comfortable hotel room waiting on the other side of the world. But in this pandemic-stricken time, the familiar sentence appropriately qualifies ‘safety’ over other words that could be used, “to make your flight comfortable” springing immediately to mind. And yet it is the airline and hospitality industries (who have made businesses out of appealing to one’s need for comfort) that are desperately in need of balancing being approachable and hospitable; with being distant and potentially ‘sterile’. This will become increasingly apparent as the lockdown lifts and business resumes.

So what will be the complexion of hospitality environments post-covid? And will hospitality, whose etymology evolved from the latin root hospes (and also gave us the word ‘hospital’) take a sanitized cue from its healthcare cousin that similarly provided a place of rest and recuperation?

Will my drop-off experience include not just the obligatory security check and the casual banter with the doorman but also digital bio-hazard screening? Will the warm greeting from the receptionist who name checks me on arrival, be replaced by a system not dissimilar to checking in at an airport – a non-interactive exchange of passport, credit card and verification codes with a kiosk that will dispense my key card in an impersonal fashion?

Will my (still comfortable) room have an air of the clinical or vacuum-sealed, with notifications (both digital and in gift card form) of how scrupulously the room was cleansed using anti-viral cleaning agents and electrostatic sprayers for surface sanitation? This would at least negate the 1-minute ‘wipe and vacuum’ turnaround service and instead resemble something more akin to a sterilized crime scene from the series CSI Miami.

Will my trip to the gym be turned into a tougher decision as I am provided with the choice of psychological well-being classes and relaxation therapies to counter the stresses and strains of borderless working patterns? My recent working pattern within a small room in my condominium in Singapore has turned me into a ‘Zoombie’ who works longer hours and cannot differentiate between the office and home life (more of this in a later article).

And will my food and beverage experience, often rich in wonderfully planned or spontaneous opportunities for discussion at the bar or buffet counter, turn into a claustrophobic à la carte dining experience, with co-presence with my guest made possible only via perspex screens and the attendance of automated service staff bearing copious sanitiser?

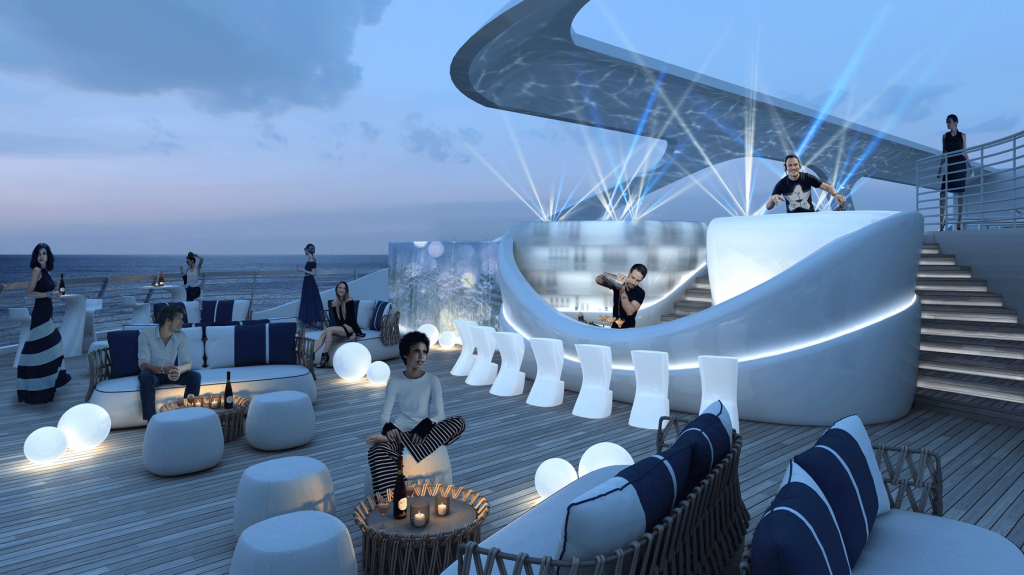

The answers to the above questions are a combination of ‘most definitely’, ‘highly likely’ to ‘probably’, according to leading hospitality experts. All those interviewed agreed that the vocabulary of what constitutes hospitality today, will need to adapt to promote safety as an equally important factor alongside comfort, tomorrow. The health and wellbeing of the hotel guest is undeniable and, like precious cargo upon a ship in stormy waters, will require a sturdy vessel, crew and an operations ‘deck’ to maintain itself and its valuable occupants. It should come as little surprise that establishing an incident command centre may similarly become a key component in the future – acting as a ‘first responder unit’ that monitors the health and wellbeing of guests. Such a facility could even be adaptable as a medical command centre if the hotel is commandeered as a healthcare facility in extremis.

This period has taught us that while the business world can continue without the need to travel, a Zoom call is no replacement for personal interaction. Whilst the frequency of business travel may initially be reduced, the very circumstances we have encountered will provide a new perspective on what constitutes essential travel. As financial markets rally and businesses emerge from the lockdown, it is not hard to imagine hotels in major cities of industry, trade and commerce similarly rallying and enjoying a return of business – albeit in a newly balanced light that embraces some or all of the safety precautions mentioned earlier. But in an almost Darwinian ‘survival of the fittest’, there will inevitably be small business fatalities in hospitality, necessitating an adaptation and evolution to the changing times. (In the UK alone, it is reported that almost three quarters of all restaurants will not survive the recent lockdown and social distancing measures).

Those trips that do take place will be essential and perhaps more meaningful; even longer. It may potentially return air travel to a time before it became a mass commodity as ubiquitous as riding a bus. Budget travel may well be a thing of the past for the foreseeable future, as travel and accommodation will become more expensive. But this imposed recalibration will make us appreciate our recreation time more. The high frequency 3-day weekend break will become a lower frequency 1 or 2-week holiday, where we may look forward to a more culturally enriching, rehabilitating and comforting experience. Yes, there will be instagrammable, consumer-friendly indulgences; but these will perhaps be balanced with the revived importance of family and friendships in our lives.

So what becomes of our newly precious leisure time? Safety is important, but we should ensure that the pandemic does not swing the hospitality pendulum far from the values and meaning of the word hospes: the interrelationship between ‘guest’ and ‘host’ that can be easily borne out of self-sustenance and green design principles that balance safety and comfort. Or, as Pomeroy Studio likes to perceive it, a sustainable balance between restraint and delight. Environmentally sustainable hotels and resorts should exercise restraint in the use of fossil fuels and artificially lit / ventilated spaces; and embrace natural light and ventilation for the benefits they offer to both the natural and manmade habitat. Arguably, Florence Nightingale’s revolutionary hospital wards helped combat the spread of infectious diseases by acknowledging that the exposure to outdoor air and sunlight played a critical role in diluting and dispersing infectious agents and greatly reducing their survival further. Ergo, “goodbye” confined ‘petri dishes’ of disease; “hello” porous environments of rest and recuperation that offer health benefits.

This brings us neatly to delight, which may not be just about creature comforts and physiological wellbeing benefits for the guest, but also the economic wellbeing for the hotel or resort itself. Making the hospitality developments’ operation truly sustainable may sound like an Aristotelian cliché (i.e. ‘the whole being greater than the sum of the parts), but it is a truism that the hotel / resort can be just one small part of bigger, more sustainable landscape. The inter-relationship between hospitality, retail, education, culture, entertainment and leisure functions can collectively help weather the drizzle of a downturn or the storm of a full-blown recession. Ultimately, this means going beyond the environmental sustainability of the hotel / resort to create closed-loop, self-sustaining economies that leverage on local culture and identity as a source of delight to provide a richer hospitality experience.

Imagine an island that in its past life might have been a plantation that eventually became an industrialised shipping port. There lies the opportunity to start by embracing the ‘natural’ and the ‘manmade’ for its cultural identity – eco trails and parks and even organic farms that allude to its plantation heritage; or retaining and converting the industrial cranes and other ancillary structures into boutique hotels that ‘riff’ off its shipping heritage – such as Hotel Faralda in Amsterdam and The Krane in Copenhagen. But going beyond these, there lies the opportunity to embrace related industries to be self-sustaining and to empower circular economies. It also allows the guest to be not just a spectator, but an actor in the sustainable food generation process – thus providing a more fulfilling hospitality experience.

Those very organic vegetable farms combine environmental conscientiousness (reducing the carbon intensive importing of food produce by virtue of home growing green spaces) with entertainment and leisure (the opportunity for guests to play ‘hunter gatherer’ for their dining experience), culture (heritage centres that curate ‘nostalgic tourism’ to celebrate past activities), education (training centres that nurture agriculturalists as well as hospitality industry professionals to gain work experience before graduating into the resort or beyond) and commercial interests (retail concepts to sell the ‘fruits’ of ones’ labours, quite literally). Waste from the farm and restaurants can very well be used for alternative purposes: for example, the Accor hotel chain purportedly uses discarded orange peel to make marmalade; and De Prael, the brewery that produces the organic beer Hemelswater in Amsterdam, uses rainwater and re-uses the hops and barley from the brewing process as cattle feed. This week, I return happily to the studio and confess that the park and supermarket barely provided a respite from my month-long lockdown. Yes, distant friendships and family bonds refreshed, but I similarly imagine that many exiting from this period of confinement feel the need for authentic and extraordinary experiences. I have no doubt that ‘happenings’, such as those created by The College of Extraordinary Experiences will be a vaccine to the monotony of lockdown in the future. And when the lockdown comes once again (and friends, we will need to be prepared, as it will), that extraordinary trip may very well be a virtual one.

For further details, please visit pomeroyacademy.sg.

Further reading: