‘Water, water, everywhere…

… nor any drop to drink’. In Coleridge’s Rime of the ancient mariner, a seafarer slays an albatross despite leading him, and his seamen, to calmer weather. Such an act of cruelty on nature was repaid with turmoil at sea and the eventual death of his crew. The seafarer was only spared death after he marveled at Nature’s beauty, but his penance was to tell his woeful tale to whomever he met. Climate Change has become our modern day albatross that, like the mariner, hangs around our neck as a painful reminder of our treatment of nature. We are bearing the consequences of our earlier actions and are compelled to tell the tale.

Most cities grew as a result of trade via water, hence why the majority of cities with over 10 million inhabitants are located by a lake, river, or ocean. As the global population increases and the trend continues towards inner city migration, cities have become denser, and land more scarce – their real estate values soaring ever higher. But with increasing prosperity comes the proportionate risk of more financial as well as physical damage caused by rising sea levels and more frequent flooding.

Most cities grew as a result of trade via water, hence why the majority of cities with over 10 million inhabitants are located by a lake, river, or ocean. As the global population increases and the trend continues towards inner city migration, cities have become denser, and land more scarce – their real estate values soaring ever higher. But with increasing prosperity comes the proportionate risk of more financial as well as physical damage caused by rising sea levels and more frequent flooding.

The value of New York City’s buildings, transportation, and utilities infrastructure currently at risk from storm surges and flooding (such as Superstorm Sandy in 2012) is an estimated US$320 billion. But according to continuing studies by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), this figure will increase to US$2 trillion by 2070.

By 2050, it is estimated that 40% of the global population will be living in river basins that experience severe water stress, particularly in Africa and Asia. Waterfront cities, like Miami, will become increasingly depopulated or even abandoned, as the traditional, static responses to flood defense (i.e. barriers or raised accommodation) lack adaptability. As a result, the global population will migrate to cities in higher and cooler plains in the wake of extreme temperatures, food shortages and heightened flood risks. The world’s waterfront cities will need to adapt if they are to continue to provide adequate living standards for their citizens.

Waterborne communities, made possible by a combination of floating or pier architecture may present an answer to future urban growth that will alleviate urbanisation pressures in over-populated inner city centres, which, by 2050, will house 70% of the global population. Changing the perception of water-based communities is a fundamental step in creating more sustainable urban developments that can accommodate water level rise, rather than ‘conflict’ with it. With over two-thirds of the Earth covered by water, this domain could be a viable alternative to sustainable urbanisation in the 21st century.

Waterborne communities, made possible by a combination of floating or pier architecture may present an answer to future urban growth that will alleviate urbanisation pressures in over-populated inner city centres, which, by 2050, will house 70% of the global population. Changing the perception of water-based communities is a fundamental step in creating more sustainable urban developments that can accommodate water level rise, rather than ‘conflict’ with it. With over two-thirds of the Earth covered by water, this domain could be a viable alternative to sustainable urbanisation in the 21st century.

Contrary to popular belief, waterborne development can be a preferable place to inhabit in the wake of natural disasters. As waters rise from flooding, waterborne developments can similarly rise – thus reducing flood risk. Grounded developments on the other hand are engineered to move slightly according to seismic or soil settlement influences; or may incorporate buffers to seasonal floods that act as physical water barriers at door and window thresholds.

Living on water is not a vision of a dystopian future; there are countless examples of how society has expanded into the sea, one of the most famous of which being Venice, Italy. Originally a lagoon made up of small islands, Venetians drove wooden piles into the mud, sand and clay, creating foundations that formed the base for what would become one of the most important cities of trade and commerce for 400 years. More recently, waterborne development has been eschewed towards hospitality and resort homes surrounded by water. The recently completed Lexis Hibiscus resort in Port Dixon, Malaysia, features 522 water villas – making it the largest water homes development in the world.

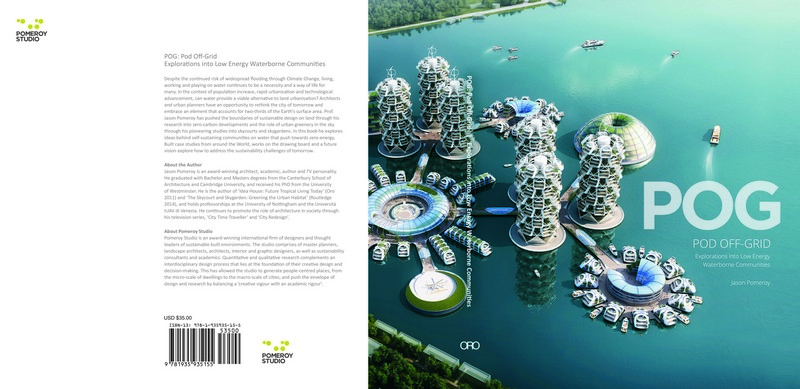

In my recent book, entitled POG: Pod-Off-Grid | Explorations on Low Energy Waterborne Communities (ORO Editions, 2016), I explored self-sustaining zero energy waterborne communities that would address many of the social, spatial, cultural, economic, environmental and technological challenges of tomorrow. Projects were conceived as a series of modular waterborne structures independent from the grid and adaptable to tropical as well as temperate climates. It also allowed for an infinite number of spatial configurations and economic scenarios, given modularity, adaptability, and diversity, making the structures deployable more rapidly than conventional development in spatially or historically constrained urban centres.

Sustainable waterborne development will help ease the pressures of population increase, urban migration, land shortage and the requisite rising land values, whilst fighting climate change related risks. Let’s hope that this will help reduce our carbon woes, and help remove the albatross hanging from our necks.