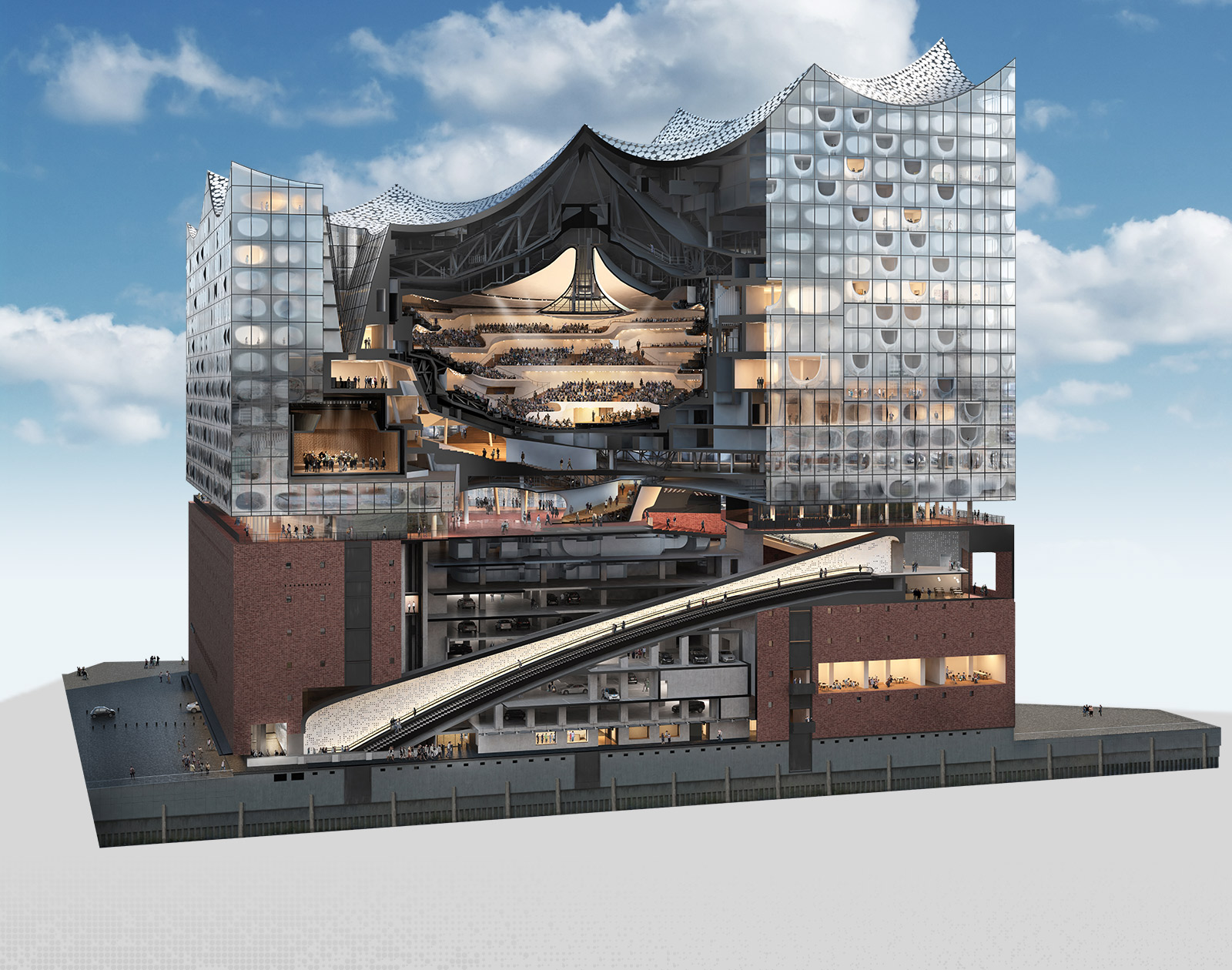

Early this year the long-awaited $832.5 million iconic masterpiece that is the Elbphilharmonie concert hall finally opened its doors to the public after ten years of construction. Set along the banks of the Elbe River in the German city of Hamburg, the ‘crystalline palace in the sky’ was built on top of the remnants of a 1960s redbrick warehouse.

The stunning design adds yet another breathtaking string to the bow of worldrenowned Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron, whose portfolio includes such architectural delights as London’s Tate Modern, and the Beijing National Stadium.

The stunning design adds yet another breathtaking string to the bow of worldrenowned Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron, whose portfolio includes such architectural delights as London’s Tate Modern, and the Beijing National Stadium.

In March it was announced that the latest addition to the Elbphilharmonie spectacle would be a 2,475 square foot penthouse on the 24th and 25th floors of the building. This is no ordinary penthouse, however, and begs a number of questions from the outset: first, based on the client brief, how does one go about implanting an organic, seamless space into a right-angled rational structure while incorporating intelligent building techniques capable of saving costs, time and resources, and minimising existing tolerances between planning and implementation on the ground?

The answer comes from a design and construction team comprising the Munich office of Bruckner Architeckten, Elphilharmonie’s interior architect Irena Richter, and Bavarian architectural wood experts Schotten & Hansen, who specialise not only in luxurious custom-made yachts, handmade wooden plank, exquisite parquet and unique interior design, but also in prefabrication technology. Founded in 1984, they are known as much for their high quality wooden floors and interiors, as they are for their cooperation with world-renowned international architects, shipyards and builders and new developments within the construction process. And this project is no different, marking the first time that the company has presented digital technology for the construction industry.

What sets the penthouse apart from the other 44 units on the property is that the anonymous buyer was prohibited from carrying out any extensive construction, as any on-site work would have created a disturbance in the operation of the Elbphilharmonie, as well as possible risk to the building’s structure. To alter the interior development in accordance to the wishes of the owner of the apartment the challenge for the designers and builders was to plan the construction so that it would not compromise completion of the final stage of the building.

The solution was for Schotten & Hansen to construct prefabricated modules to be delivered and assembled on site. Indeed, following extensive and precise drafting, over 1,000 components were sculpted off-site using robotic devices and CNC milling machines. And if this did not present a big enough challenge, all pieces needed to be small enough to be transported to the penthouse summit via the Elbphilharmonie’s passenger elevators before being fitted internally over an intricate wooden substructure.

The client brief was clear: “to invoke the instinctive cocooning of childhood for which there is no place in our optimised, pragmatic world, where one large room, a bright amorphous space fills the majority of the space.” Its rounded edges are designed to create of continuum of ceiling and walls without seams or edges, and a staircase leads to a gallery sleeping area, where parapets, counters, benches and seats grow sculpturally from the walls. Passages and views into other rooms open up and lead to the cave-like bathroom and into adjoining rooms, which also feature curved forms made from light aerated concrete.

In order to obtain the most accurate planning documents, the empty space into which the penthouse would fit was completed as an accurate computerised model. Architectural plans were created using a laser scanner into which precise measurements were inserted to create computerised scale models of the entire apartment, with 3D renderings revealing a cave-like space, void of any corners. The next step was the development of the design and installations on screen.

In order to obtain the most accurate planning documents, the empty space into which the penthouse would fit was completed as an accurate computerised model. Architectural plans were created using a laser scanner into which precise measurements were inserted to create computerised scale models of the entire apartment, with 3D renderings revealing a cave-like space, void of any corners. The next step was the development of the design and installations on screen.

The process involves the computer then decomposing the organic forms of the wall and ceiling shells and the mushroom-like columns into individual parts. The result is a modular building system that can be reassembled on site. Indeed, with no sawing or drilling required, each part is made to fit perfectly together, reducing the time needed on site to a minimum. Technological advances mean that every detail, including any deviation from building intolerances, are finalised in advance in the 3D model, and construction is a case of assembling the prefabricated elements on site.

While today’s building industry characterised by the materials and products that are constantly evolving to the highest standards, the methods used for construction over the past 100 years have also changed considerably. Despite technological advances, the majority of today’s construction processes are still based on two-dimensional representations, where the process involves several stages before implementation and is susceptible to deviation. In this project however, no expense has been spared as plans and any necessary changes can be adapted in real time and distributed to all parties involved in the project. And while the high-tech method of thorough planning and manufacturing on the basis of spatial 3D computer models is already commonplace in machine and automotive building, in the building industry it remains in its infancy. Indeed, it is common for an interface to take place between design planning and execution, however any architect will no doubt agree that computer generated 3D planning has decisive advantages compared to 2D drawings, as all the craftspeople and planners involved are able to use the same data. The result is that tolerances can be identified at the earliest stages and changes can be adapted in real time and distributed to all parties involved.

In the case of the Elbphilharmonie penthouse, floor-to-ceiling expanses of glass surround the spectacular space continuum that is formed beneath the vaulting roof of Hamburg’s latest landmark. From the on-site installation of the computer-generated wooden substructure, to the electrical cables and pipes that precede the plastering of the prefabricated parts with a fine-grained breathable material, the result is a stunning and wholly homogenous surface made of lightweight aerated concrete and plasterboard, cut with tolerances that show details down to the nearest millimetre, and no doubt give us an extraordinary insight into the future and possibilities of prefabricated construction.